|

The Sublette County Journal Volume 2, Number 25 - July 17, 1998 brought to you online by Pinedale Online

Hoback Canyon, 1895 by Judy Myers One hundred three years ago, almost to the day, Hoback Canyon's Battle Mountain area was the scene of a confrontation between a posse of Jackson Hole men and a small band of Bannock men, women and children. One of the possemen, Stephen Leek, wrote: "we had asked in vain for years that the Indians be kept up on their reservations and no attention had been paid to the request; just as soon as one Indian was killed, we were the center of all eyes". A New York newspaper of 1895 ran this sensational and totally false headline: "ALL RESIDENTS OF JACKSON HOLE, WYOMING MASSACRED." Actually, it was the residents of what is now Bondurant that were closer to the action. First, a little background. In 1868 the United States government signed a treaty with the Shoshone Indians under Chief Washakie and the Bannocks from Ft. Hall, Idaho. This agreement gave the Indians the right "to hunt upon the unoccupied lands of the United States so long as game may be found thereon and so long as peace subsists...." The Shoshone Indian agent, Captain Ray, wrote that hunting was necessary because the "ration for Indians on this reservation...is not sufficient to ward off the pangs of hunger. ...They will resort to desperate methods before they will go hungry...no power can prevent them from killing game or cattle". Both the Shoshone and Bannock tribes had used the Fall River Basin, now commonly called Hoback River Basin, and Bondurant area as hunting grounds. A few settlers had been moving into this area and by 1892 the Daniel Faler family was ranching there. Vint Faler, interviewed by Crowell Dean in the 1930s and Faren Faler, at the request of Ethelyne Worl in 1985, have told of an incident that occurred just three years before the Jackson Hole posse took action. Both accounts are in Harold Faler's personal files. In the early 1890s Indians shared the country with the Falers and other settlers and they often traded. The Indian men hunted and sometimes gambled on horse races or cards with the white men. The Falers had always been friends to the Indians, but when the government began forcing them to stay on the reservation, the Indians, according to Vint Faler "went on the war path, stole horses and terrorized the country." Faler Brothers Captured by Indians In this setting two of the Faler boys, Vint and Arthur, had gone out from the ranch to round up cattle. Arthur had a race horse and Vint had a saddle horse which they knew the Indians wanted, so when night came they picketed their horses, and rolled up in their saddle blankets nearby for the vigil. Early the next morning both horses were gone. According to Vint, he and his brother set out on other horses to track their prize mounts. As they rode near the head of Cliff Creek, they were suddenly surrounded by whooping Indians who took the boys to their camp. Vint and Arthur were tied to a tree and brushwood was piled at their feet in preparation for being burned. One of the young Indians, a friend of Vint's, spoke on behalf of the whites. As the talking continued, the prisoners were fed dog meat. After much debate, it was decided to allow Vint to go free, but not Arthur. The reason for this was that in the past Arthur had raced his horse against the Indians' horses. When he lost, Arthur would get angry and insulting. When he won, he would harass the Indians. He was, therefore, not popular. Vint, on the other hand, "had been their friend, breaking tough horses for them and not winning games so consistently as his brother." Vint refused to leave without his brother and used all his persuasive powers to free Arthur. After more arguing, both brothers were finally turned loose with the horses they had been riding, but not with the stolen ones.

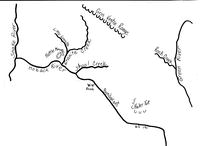

Events were soon going to impact the Indians' nomadic lifestyle. Wyoming became a state in 1890. In January, 1895, the Legislature passed stringent game laws with closed seasons on big game and a requirement that non-residents buy a hunting license. Most Indians were unaware of the law or claimed exemption by the federal treaty of 1868. For many years settlers had complained that the Indians were slaughtering wild animals simply for the hides. The Secretary of the Interior issued a circular in 1889 to "impress upon the minds of the Indians...that the wanton destruction of game (would) not be permitted. The time has long since gone by when Indians can live by the chase. They should abandon their idle and nomadic ways...and adopt civilized pursuits." In answer to the circular, Captain Ray, Agent for the Shoshone, said that not a single case of wanton destruction had ever come to his knowledge and that "It is a well-known fact that the extermination of the buffalo...was the work of the whites, principally." Thomas Teter, Indian agent for the Bannocks at Fort Hall also believed there was no wanton slaughter by the Indians and that it was "a notorious fact that hundreds of animals are killed by white men for nothing more than heads and horns." The United States District Attorney inquired into the unconcealed hostility of the Jackson Hole people against the Indians and reported that 25 or so settlers had lucrative businesses as professional guides for tourists and hunting parties. Hunting by Indians threatened to deplete the region of deer, elk, and moose and that would jeopardize their occupation as guides. One man told Agent Teter that he made $800 during one season of guiding hunters. Marysvale (now Jackson) settlers had done everything they could to force the Indians to stay on their respective reservations and not hunt in `their' region. Armed with the new game laws, the citizens made careful plans to keep the Indians out of the Hoback and Jackson area. According to Mr. Pettigrew, U.S. commissioner at Marysvale, "At our last election the question of keeping out the Indians was the most important one. Officers...were selected because we knew they would take steps to help us keep the Indians out." Constable Manning added, "We knew very well we...would bring matters to a head. We knew someone was going to be killed...(and then) we could get the matter before the courts." Fort Hall Agent Teter called it a "preconceived scheme...to induce the Department to prevent Indians from revisiting Jackson Hole country." Teter's chief clerk at Fort Hall, Ravenel Macbeth, in a sworn affidavit said that Marysvale Justice of the Peace, Frank Rhoads, (sic) wrote to Wyoming Governor W.W. Richards asking for protection "in the event of trouble with the United States authorities over the arrest of Bannock Indians." Gov. Richards told Rhoads to "enforce the laws of Wyoming, put the Indians out of Jackson's Hole, to keep them out at all costs, (and) to depend upon him for protection." Rhoads then issued warrants for the arrest of Bannock Indians hunting in Wyoming. Indian Arrests Begin According to Marysvale citizen Stephen Leek, the officials began enforcing the game laws and several Indians had been arrested and fined. The Indians, not being able to pay the fines, were to be taken to the county seat in Evanston under guard. The state offered no assistance in moving the prisoners and the federal government took no notice, so it soon became an unmanageable situation. Most Indians easily "escaped." In June, 1895, three constables tried to arrest a number of Indians and found themselves "looking down the barrels of Winchesters." The Bannocks said they would not submit to arrest and were going back to their camp. The officers, outnumbered, returned home. Something had to be done or these officers would be the laughing stock of the Indians. On July 2, 1895 a posse of 38 men was formed to return to the Hoback Basin and make the arrests. Posseman Stephen Leek wrote, "The Indians would be expecting us to come from the north...so a rendezvous was selected...on the Gros Ventre river...and thence down Green river into the Hoback Basin from the east, thus taking the Indians by surprise." The Indians who had initially resisted arrest with their Winchesters had gone to the main camp of Bannocks and Shoshone and a council was held. The Shoshone, wishing to avoid trouble, left the Basin, went east to where Rock Creek joins the Green River, and unluckily camped in the path of the approaching posse. Leek states that the Shoshone "though considerably outnumbered, met the settlers with rifles in hand and six shooters at their belts, and made considerable resistance...A spark would have brought on a battle...(but) the settlers secured all the Indians' guns and quiet was restored." The entire camp of "squaws, papooses and men...camp duffle and about 70 head of horses" was taken to Jackson. The men were tried and convicted of illegally hunting in the state. And then the troubles increased. Realizing that they had not captured the Bannocks, 27 possemen started out again to bring in the ones that had refused arrest on July 2. The posse traveled by way of Cache Creek and Little Granite Creek. The Indians were located on the Hoback River. Leek states, "we awakened at 4 am...traveled silently on foot...completely surrounded the camp (and) when it was finally light enough for us to see our rifle sights we...made our presence known." The Indians gave up gracefully, and the entire camp of 9 men and their families, all mounted, began the trip to Jackson under heavy guard. Leek states that treachery was suspected and the Indians were surly. After the noon break, at about the present location of the Historical Marker, where the Hoback Canyon begins to narrow down (the northwest end of Bondurant), the Indians all changed to fresh horses. Eye-witness Leek continues, "The outfit was passing through timber where a single trail wound among the trees when, at a prearranged signal, a whoop, the application of the spurs and quirt, a number of scattering shots, a few bucking horses, some few flashing glimpses through the trees of flying bodies in the timber to our right - and our Indians were gone!" One Indian had been killed and another wounded. An Indian woman had been knocked off her horse by a low branch. She fled on foot leaving behind a young papoose who was taken to nearby settlers until he could be returned to Fort Hall. Bannock Agent Teter's later report of August 7, 1895, stated that two papooses were lost and only one was found alive. "The other papoose, being only 6 months old, has undoubtedly perished." After unloading the Indians' pack horses, leaving the equipage in a pile and turning the animals loose on Granite Creek, the posse rode for home. News Spreads

Rumors flew. Augusta Paulina Bayer was living on the Nowlin Place south of Big Piney at that time and wrote in her memoirs, "word came through the grape-vine that Sitting Bull and his Indians were in the Hoback Basin country and were on the war-path, headed toward our part of the country. Some of the women were scared and were making preparations to leave, and wanted me to go with them, but I did not believe the report and said I was going to stay. They never came and the rumor was all wrong." Back in Jackson, federal troops were requested. Posseman Leek stated, "Infantry and cavalry were started for the seat of war. A negro company in trying to get their wagons over Teton Pass, found that the mules could not pull them, so the mules were unhitched, long ropes tied to the wagons and the negros pulled them up by hand." These were the only troops that made it to Jackson Hole and they found everything to be peaceful. Fort Hall Agent Teter also went to the Jackson area. On July 24, 1895 he verified that there were about 200 Indians, 50 of whom were Bannocks, "encamped in Hobacks Canyon or near Fall River, 35 miles southeast from Marysvale". Teter reported to the Department of the Interior, "The Indians have for many years gone to the Jackson Hole country in search of big game, and it is only since the business of guiding tourists...has become so remunerative that objection has been made to their hunting in Wyoming....Settlers last year stated that if Indians returned for big game this season they would organize and wipe them out, the settlers looking upon big game as their exclusive property." The United States Attorney General's report stated "On July 4...eight Bannocks (Stephen Leek said Shoshone) were arrested on Rock Creek near the head of Green River and taken to Marysvale, where six of the party were fined $75 each and costs, the total amount of fine and costs being about $1400. This the Indians were unable to pay, and they were placed under guard to await instructions...(but) officers relaxed guard duty over the Indians who escaped." "The next arrest of Indians was made July 13...From an interview with Nemits, an Indian boy...and from interviews with several of Mr. Manning's posse, I learned that the constable and his men told the Indians some of them would be hung and some would be sent to jail...The constable also said in the hearing of the Indians, that if the Indians attempted to escape the men should shoot their horses...The captors did not care particularly about getting their prisoners safely to Marysvale, but on the contrary tempted the Indians to try to escape." The Indians' and Other Accounts of the Incident Ben Senowin, a Bannock Indian, made a sworn affidavit that he was in the company of 8 other Bannock men, 13 women and 5 children on July 15 when their camp was "feloniously assaulted and by force of arms attacked by a party of 27 white men." After surrendering and being marched 30 miles towards Jackson, Senowin "saw several of the white men placing cartridges in their rifles and believing his own life and the lives of the members of his party to be in danger, called upon his people to run and escape whereupon the white men, without just cause or provocation, commenced to fire." Senowin saw an old man fall dead, 20 year old Nemits wounded and one infant lost. Senowin and his friends also lost seven rifles, 20 saddles and blankets, one horse, 9 packs of meat, and 9 tepees. His report claims that the Indians were not told why they were assaulted, nor were they aware of any crime committed. Another version of the July 15 incident was Indian Agent Teter's report: "A hunting party of nine Indians, with their families and camp equipage...were surrounded by an armed body of settlers, numbering 27, who demanded of the Indians their arms. The Indians, upon surrendering their arms, were separated into two parties; the males, under a guard...(and) their families, pack animals, etc... The Indians, roughly treated, were driven throughout the day...and as evening closed in the party approached a dense wood, upon which the leader of the settlers spoke to his men, and they examined their arms, loading all empty chambers. The Indian women and children, observing this action, commenced wailing, thinking the Indian men were to be killed...passed the word ...to run when the woods were reached. The Indians, concluding their last hour had come, made a break for liberty; whereupon the settlers without warning opened fire, the Indians seeing two of their number drop. "The following morning the Indians, having gathered together, found they were minus two men and two papooses, and revisiting the scene of the shooting, could not find their people or their belongings, upon which they returned to the reservation. "One of the two men supposed to have been killed (Nemits) was recently discovered by scouts. He had been shot through the body from the back...and had crawled to a point several miles distant from the place of the shooting, subsisting for 17 days upon the food which he had in his wallet at the time he was shot." Another official report said that Nemits "crawled for three nights to reach the ranch of a man friendly to Indians, and was 17 days without medical attendance." Neal Blair, in his wildlife history book, states that Constable Manning found the wounded Indian and took him to the Faler Ranch. Vint Faler's account, told to Crowell Dean, agrees closely with the official reports: "In the flight of the Indians, one papoose was left, a small boy of about six years was picked up and brought to the Faler ranch...The Indian Police came for the boy in a few days, and took him to the reservation. Thirteen days after the fight Mr. Vandervort and Mr. Dodge brought a wounded Indian brave to the Faler ranch. He had been shot through the hip and a rifle bullet had coursed through his intestines. For 13 days, and without food, he had cared for himself in the mountains. At the Faler home he was carefully treated until he was strong and the Indian police came and took him to the reservation." An August 2, 1895, New York Evening Post article stated that at the July 15 altercation, Constable Manning had reason to believe the prisoners would escape and gave orders to shoot their horses. No horses were shot, however. The Indians had been arrested for a $10 and 3-month-imprisonment offense. When Manning was asked if he felt this offense justified killing them when they attempted to escape, he answered, "I would consider that my right." The United States District Attorney report of the incident included an interview with Constable Manning. Asked why he didn't just let the Indians go, wait until they returned to Fort Hall and then arrest them, he said that the agent there would probably not give them up. Constable Manning also said that Timeha, the nearly blind, old man who was killed, had been "shot in the back and bled to death." Battle Mountain Is Named The incident has been called a "massacre," a "war," and a "battle." The "massacre" headline was erroneous. There certainly was not "Bannock War." As Gordon Johnston wrote in his February, 1989 Roundup column, "To my way of thinking, a battle has to have folks on both sides doing some shooting. We'll have to call the incident a nonbattle." Nor did it take place on what we call Battle Mountain. But it did happen in that area. Belligerence Subsides Early public sentiment in favor of the whites, changed in favor of the wronged Indians. On August 14, 1895, Agent Teter requested that his Indians be given employment and increased rations. The Department of the Interior immediately ordered this done. In September, a party of 8 Indians with an escort of soldiers went to Jackson's Hole to retrieve their property. Two weeks after the Battle Mountain incident, the situation had settled down. The Tenth Calvary (black) had arrived at Marysvale but the Infantry had been told to turn back. The settlers left their fortifications. The Bannocks had returned quietly to their reservation at Fort Hall without any retaliation and their Agent Teter wired to Washington, DC that he was instructing his Indians on the provisions of the Wyoming game laws "of which they have been entirely ignorant." Teter also claimed that the "lawless settlers" were the guilty party, not his Indians. Constable Manning and some of his possemen later appeared before a grand jury in Cheyenne where they were cleared of all blame in the matter. U.S. Supreme Court Decides Hunting Privileges Question The Indian Bureau, desiring to have the hunting rights determined in court, requested that "one of the Indians who had escaped the bullets of the Jackson's Hole posse surrender himself . . . for trial." Bannock Chief Po-ha-ve, known as John Race Horse, agreed to test the legality of the new Wyoming state game laws. He admitted killing 7 elk on unoccupied and unsettled land in the Hoback area and submitted to arrest for killing game out of season. On Nov 21, 1895, Judge John Riner heard the case and in a 25-page document decided for the Indians. Judge Riner ruled that the 1868 treaty rights held precedent over Wyoming law and the state game regulations did not apply to Indians. Race Horse was free. The case was appealed to the United States Supreme Court and on May 25, 1896, Judge Riner's decision was reversed. It was argued that when the hunting area ceased to be a Territory and became a state, it came under the authority and jurisdiction of said state. The right to hunt ceased when the United States parted with title to the land. The hunting privilege granted by the 1868 treaty was temporary and precarious, not perpetual. In opposition to this view, it was argued that statehood had been anticipated at the time of the treaty and Congress still assured the Indians the right to hunt because hunting was not for sporting purposes, but for the Indians' chief source of food. Statehood would not impair or negate rights granted by a sovereign power. Except as cattle range, the hunting lands were still, as the treaty stated, "unoccupied." The Supreme Court of the United States decided against the Indians, stating that their treaty was repealed by the act of Congress that admitted Wyoming as a state into the Union. Indians must henceforth observe the game laws of Wyoming. In effect, the Bannocks and Shoshone could no longer hunt unrestricted and all wildlife now belonged to the state. According to Neal Blair, this episode "was probably the salvation of the game herds in northwestern Wyoming." Race Horse was given to the custody of Uinta County Sheriff John Ward in Evanston. Sheriff Ward was ordered to fine Race Horse $122.75 plus his costs. Judge Riner issued testimonials as to the good behavior of Race Horse and the Indian Judge Ty-hee. The Indians were sent back to their reservation and were no longer allowed to hunt on Wyoming's "unoccupied" lands. Hoback Canyon's Battle Mountain retained it's misnomer and the case was closed. Sources: Permission was granted by the Wyoming State Archives, Department of Commerce to use the excellent article "1895 Report of Indian Affairs Commissioner" in Annals of Wyoming, Vol. 16, #1, January, 1944 and the W.P.A. articles by Stephen Leek and Crowell Dean (the latter an interview with Vint Faler). Permission was granted from Harold Faler to use his personal files; from the Pinedale Roundup and Gordon Johnston to use "Lodgepole & Sagebrush", 2-16-89; from Wyoming Tribune to use May 26 and July 21, 1896 articles; from Neal Blair to use History of Wildlife Management, 1987; from Nancy Reinwald to use "My Three Score Years and Twelve", by A.P. Bayer and from Jackson Hole Historical Society to read their files. Other sources used were: Supreme Court of the United States report, October term, 1895; Cheyenne Daily Sun-Leader, Aug 2 & 3, Oct 4, Nov 21, 1895; News-Register, Evanston, March 14 & July 25, 1896; Wyoming Place Names, Mae Urbanek, 1967; New York Evening Post, August 2, 1895. Other references to this incident may be found in Jackson Hole Guide, 5-27-1965; Wyoming Wildlife, "Makin' Smoke", by Greg Smith, Jan. 1957; Wyoming Geological Association Guidebook, 1956; Roundup Vacation Edition, 1976. Photo credits: Sketch by Lorraine Leavitt, Map by Judy Myers, Sketch by Terry Quinn See The Archives for past articles. Copyright © 1999 The Sublette County Journal All rights reserved. Reproduction by any means must have permission of the Publisher. The Sublette County Journal, PO Box 3010, Pinedale, WY 82941 Phone 307-367-3713 Publisher/Editor: Rob Shaul editor@scjonline.com |